Ontario has taken a significant step towards ensuring that people who cause injuries and deaths on our streets will face consequences that match the seriousness of their offence. Too often, when people walking and biking are killed by someone driving, the punishment handed out is incredibly small — a fine of $100, with no license suspension, no jail time, no community service, and no driver training required. The offender is also not required to attend the hearing, meaning that the families of those killed are often left to read out their victim impact statements without the person responsible present. In the fall of 2017, not just one, but two new pieces of provincial legislation were proposed to address this problem.

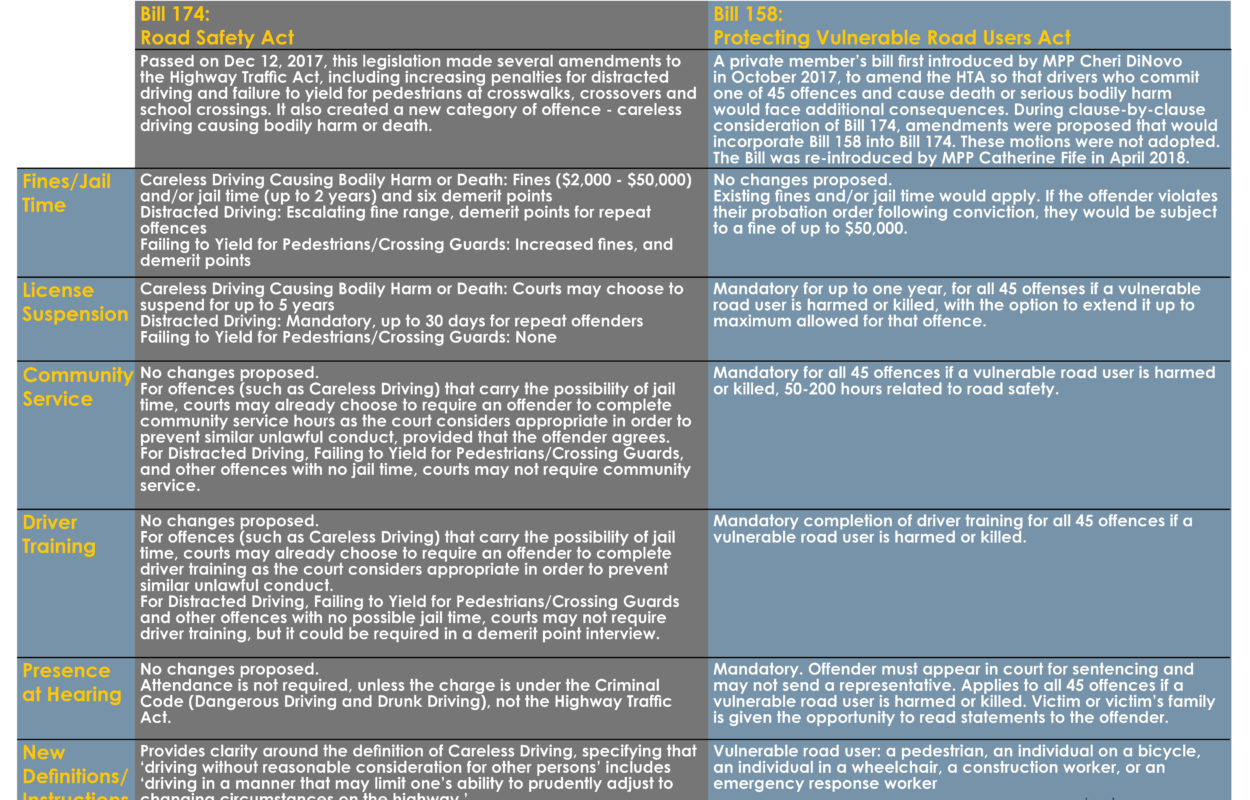

In September, Bill 158, the Protecting Vulnerable Road Users Act, was put forward as a private member’s bill by MPP Cheri DiNovo. It would have applied to 45 offences under the Highway Traffic Act, and would have added consequences for drivers who commit one of these offences and kill or seriously injure a vulnerable road user.

In October, the Liberals proposed Bill 174, the Road Safety Act, as part of a larger piece of legislation dealing with marijuana. Among other things, it amended the Highway Traffic Act

During clause-by-clause consideration of Bill 174, amendments were proposed that would incorporate Bill 158 into Bill 174. These amendments were not adopted. After a prorogation of the Ontario Legislature, Bill 158 was re-introduced by MPP Catherine Fife in April 2018.

When they were first introduced and still today, confusion has reigned in many of the discussions surrounding these two bills. Worryingly, there was also very little clarity about what the existing laws encompassed in the first place. At TCAT, we decided to take a deep dive into this question and see if we could come up with a clear answer.

To start, what did the laws allow, pre-December 12th? Could a judge, for example, require that a person who had committed a driving offence, who had maybe even killed someone, perform community service? Take a driver training course? Have their license suspended? The answer is, it depends on the offence.

We can divide Ontario’s Highway Traffic Act into two categories: jail time and no jail time (see our VRUL Legislation Comparison Chart for a more in-depth analysis). Offences that carry the possibility of jail time include Careless Driving, Racing and Stunt Driving, Driving Under Suspension, Failing to Slow Down or Change Lanes for Stopped Emergency Vehicles, Failing to Stop for a School Bus, and a few others (note that Driving Under the Influence and Dangerous Driving fall under the Criminal Code of Canada, and not the Highway Traffic Act). In addition to fines and/or possible jail time, these offences almost all carry the possibility of a license suspension. Driver training could be imposed as a condition “appropriate to prevent similar unlawful conduct or to contribute to the rehabilitation of the defendant.” A judge could also require community service, but only if the defendant agrees to it.

The second category of Highway Traffic Act offences, where no jail time is possible, makes up the majority of the offences. They include Distracted Driving, Failing to Yield to a Pedestrian in a Crosswalk, Speeding, Failing to Obey Stop Signs and Traffic Signals, Unsafe Passing, Improper Turn, Following Too Closely, Dooring, Passing a Streetcar whose Doors are Open, and many, many others. For almost all of these offences, the only penalty a judge can impose is a fine. Only a couple allow a license suspension as well. None allow community service or driver training to be part of the sentence.

The trouble with the system as it works now is that the majority of the charges laid fall under the second category. Even in situations where a person walking or biking has been hurt or killed, the person driving is generally convicted of something minor, such as ‘turn not in safety’ or ‘leaving the roadway unsafely.’ The penalty is a small fine, frequently $100 or less. More serious charges, such as careless driving or dangerous driving, often fail to stick thanks to a Supreme Court ruling back in 2008, which found that a momentary lapse of attention or a few seconds of negligent driving was essentially ordinary driver behaviour. As such, it cannot be considered dangerous, even if it results in a driving infraction and someone’s death. People accused in these cases can successfully plead down their careless driving charge to something with only a fine attached, or are acquitted, as in the recent case of a man who crossed a bike lane, mounted the sidewalk and killed a woman because he reached down to pick up a water bottle while driving.

The two legislative proposals we saw last fall both attempted to address these scenarios (see the Recent Legislative Approaches chart above). The Road Safety Act (Bill 174) introduced mandatory license suspensions for distracted driving (three days on a first offence, seven days for a second offence, 30 days for all subsequent offences) and higher fines for distracted driving and failing to stop for pedestrians and crossing guards. As a result, Ontario now has the toughest penalties in Canada for distracted driving.

It also created a new category of offence: Careless Driving Causing Bodily Harm or Death, which bumped up the penalties for careless driving in the scenario where someone is harmed or killed: up to $50,000, up to two years in prison and up to five years of license suspension are now possible (as we saw before, driver training and community service are already possible sentences for careless driving convictions). Additional instructions are given for sentencing, directing courts to consider as an aggravating factor the vulnerability of the victim, including if they were a pedestrian or cyclist.

To be effective, this strategy relies on drivers being charged with careless driving, which as we’ve seen, is typically not the case. The legislation includes a new definition, clarifying that careless driving includes “driving in a manner that may limit one’s ability to prudently adjust to changing circumstances on the highway.” This definition may lower the standard of ‘carelessness’ and help more of these charges stick (which, in turn, would encourage police forces to lay them more frequently). We will have to wait for the first court case to see how it will be interpreted, but this legislation could be a significant game-changer for enforcement and justice moving forward.

The alternative proposal, the Protecting Vulnerable Road Users Act (Bill 158), added a definition of vulnerable road users as people walking, cycling or using wheelchairs, as well as construction workers and emergency response workers, and increased penalties if someone in this category has been harmed or killed. Sentences would include the applicable fine and/or jail time outlined in the Highway Traffic Act, as well as a mandatory license suspension up to one year, mandatory 50 to 200 hours of community service related to road safety, and mandatory driver training. These penalties would apply to 45 offences, including Careless Driving, Distracted Driving, Unsafe Passing, Improper Turn, Leaving the Highway Unsafely, Failing to Stop and Speeding. Essentially, no matter what the charge, if a person who is vulnerable has been killed or injured, the driver would have their license suspended, would have to take driving lessons, and would have to perform community service. Similar laws already exist in some states, including Connecticut, Delaware, Florida and Washington.

There’s one more important piece to this equation which goes beyond penalties and has to do with being heard. Currently, there is no requirement in the Highway Traffic Act for a person who has killed or hurt someone while driving a vehicle to appear in court. Even if they’ve received a summons, the offender can send a representative (their lawyer), instead of going themselves. The families of those killed are left in the unenviable position of reading out victim impact statements without the person responsible present to hear. Bill 158, the Protecting Vulnerable Road Users Act, would have made it mandatory for the person convicted to personally attend the sentencing and hear these statements read out.

Having two pieces of road safety legislation proposed from two different political parties in such a short time is definitely a bright light and a sign of how much our perspective has shifted in the past few years. Senseless deaths on our streets are no longer acceptable. They’ve been the norm so long, though, that even with this step forward with Bill 174, there is still more to be done, through legislation, infrastructure, education and enforcement, before our streets are truly safe.