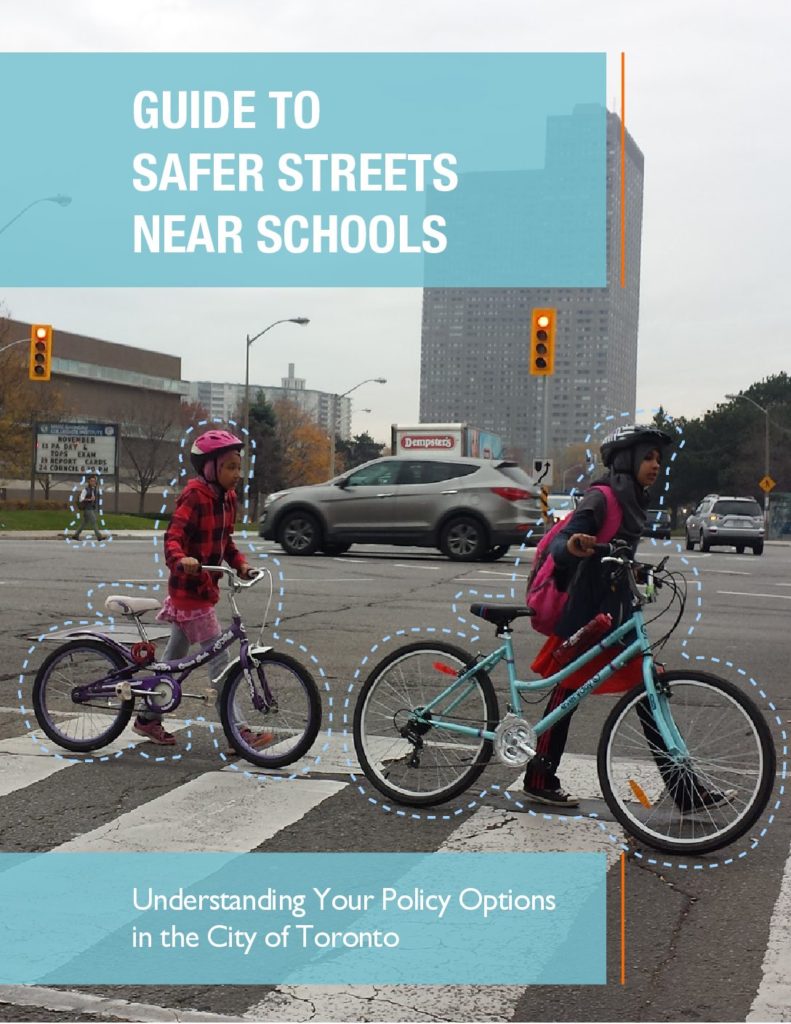

Do you want safer streets in your neighbourhood?

A Guide to Safer Streets Near Schools will help you learn how to create them. This guide brings together a number of policies from the City of Toronto that residents can use to request street improvements. It explains the policies step-by-step, and shares advice about which ones may be most relevant to you.

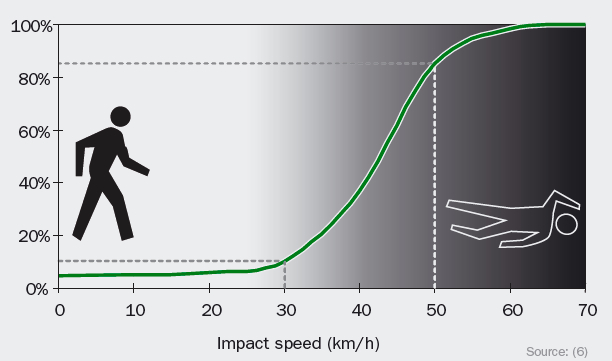

After reading this guide, you will be better informed about the importance of active transportation (getting around using your own energy, such as walking, cycling, or using a scooter, wheelchair or roller-blades). You will also learn how you, as a resident, can contribute to neighbourhood changes that slow the speed of vehicles and make it safer for people to cross the street.

Download the guide below, or explore its sections by clicking these links: