Toronto is experiencing a crisis in road deaths – the former Chief Planner, Jennifer Keesmaat, called it a “state of emergency”. New York City, on the other hand, has recently achieved impressive reductions in road deaths and serious injuries. This past year, 2017, was the fourth consecutive year of declining traffic fatalities, with the fewest New Yorkers lost to traffic collisions since 1910. This is strongly counter to national trends which are similar in Canada and Toronto.

How did they do it? They had a clear plan, promoted by strong leadership and supported by sufficient, sustainable funding. Their plan is rooted in an approach called Vision Zero, which looks at traffic deaths not as ‘accidents’ but as failures of street design.

Toronto has also released a Vision Zero Road Safety Plan, but has not yet seen the results that NYC has. Fatalities decreased by 19% in 2017, but remain higher than they were just 10 years ago. In the two years since we have committed to Vision Zero, over 100 people have been killed on Toronto’s roads.

In June, a coalition of active transportation groups launched #BuildTheVisionTO: Safe and Active Streets for All, a set of 15 municipal election priorities for building streets where people of all ages and abilities can get around actively, sustainably and safely. These are specific, concrete actions that Toronto could take to effectively make Toronto’s streets safer. Some, like increasing red light cameras and lowering speed limits, are small actions that can make a big difference. But we also need big actions that will make a huge difference: Priority #14 is to increase our funding of Vision Zero to match with NYC. New York City currently spends $38 per capita on Vision Zero. Toronto City Council voted to increase Toronto’s Vision Zero budget at the end of June, and spending in 2018 is now at about $15 per capita. If we matched NYC’s funding, think of what could be achieved!

New York’s Vision Zero Plan in a Nutshell

New York City’s Vision Zero plan is based on four straightforward principles:

- There is no acceptable level of death and injury on our streets.

- Traffic deaths and injuries are not accidents, but crashes that can be prevented through enforcement, education and design.

- Dangerous driver choices are the primary cause or a contributing factor in the majority of pedestrian fatalities.

- The public should expect safe behavior on city streets, and participate in a culture change.

The major elements of both NYC and Toronto’s plans are education, enforcement, and design changes.

1. Education and dialogue

NYC’s success has come from a broad diversity of projects and initiatives which involve the public at every step of the way. Community members play an essential role in Vision Zero. For one thing, road users are often in the best position to know about hazardous situations and to come up with creative solutions.

New York City kicked off its project with a map where community members could submit enforcement or road design comments in specific intersections and corridors, and received over 10 000 comments. This feedback was incorporated into neighbourhood safety plans. And they maintain a map on an ongoing basis which tracks not only collisions, but safe street design initiatives, speed limits, and outreach activities. Toronto also has a map, which shows collision data and safety interventions, but is not an interactive reporting tool.

Road users also must be aware of their responsibilities, and NYC’s generous funding of Vision Zero allows for extensive and ongoing education and outreach. Public information campaigns share easily-understood graphics to illustrate important and frequently-misunderstood safety rules.

These campaigns are supported by targeted, specialized sessions offered to groups and institutions such as schools, corporate headquarters and government offices, houses of worship, seniors centres, and through hands-on demonstrations at public events.

Street teams are placed at high-crash and high-density intersections and corridors, watching for dangerous behaviour and ensuring road users understand what’s required of them. These are followed up the next week by enforcement teams which issue tickets for rules violations.

Education also extends to the City’s own fleet of drivers, including employees from the New York City Housing Authority and the District Attorney’s office. In 2017, over 6,000 transit operators, 35,000 for-hire vehicle operators and 11,000 City fleet operators underwent driver training with a Vision Zero focus. Moreover, the City has committed to a policy of safe procurement, meaning that all vehicles purchased must include the best available safety technology, including truck side guards.

2. Law enforcement, Legislation and Technology

New York City’s law enforcement community has made excellent use of data to end a culture of dangerous driving. Using collision data, they identified the six violations most likely to kill or injure New Yorkers: speeding, failing to yield to a pedestrian, failing to stop on a signal, improper turning, using a cell phone, and disobeying signs. The police department has focused its traffic enforcement efforts on these six ‘Vision Zero’ violations, with the goal of “changing the current motorist culture that too often ignores drivers’ roles in creating dangerous conditions” (Vision Zero Four Year Report).

On the technology side, increasing the use of red light cameras has had a significant impact on safety. Intersections where red light cameras were installed saw a 20% decline in all injuries, a 31% decrease in pedestrian injuries, and a 25% decrease in serious injuries in the three years after installation. In addition, the City installed speed cameras at school zones, and found that speeding at these locations dropped by 63% in the first two years.

In 2014, the City also enacted a Right of Way Law, making it a misdemeanor to injure people walking or biking who have the right of way. This gives officers an additional tool to hold drivers accountable, and over 2,000 summons and 34 arrests were made in 2017 for violations that in the past would have seen no charges laid. While the summons are often pled down, the finding of guilt has positive implications for victims seeking compensation from insurance companies or in a civil suit.

3. Street design improvements

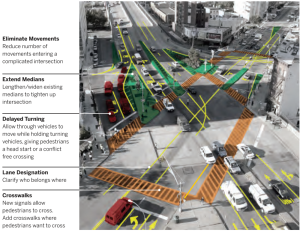

The biggest investment we can make is in designing and constructing streets and infrastructure to make it easier for all road users to make safe choices. In New York, places where the Department of Transportation has made major engineering changes have seen a decrease in fatalities of 34%, twice the rate of improvement at other locations. Street re-designs have included adjusted signal timings (such as leading pedestrian intervals, or LPIs), improved street geometry and markings, extended medians, and restricted turn movements. Here are two examples from the DOT.

Jackson Ave, Long Island City, Queens

A combination of new high visibility crosswalks, reduced crossing distances, turn restrictions, leading pedestrian intervals, extended medians and clearer lane designations eliminated 63% of all injury crashes at one intersection.

Macombs Road, the Bronx

On Macombs Road, redesign led to 41% fewer crashes with injuries.